The last thing my father told me as he pushed me from the train was “You run. I know you will stay alive, you have the Belzer Rebbe’s blessing.” He was very religious and he believed this.

The last thing my father told me as he pushed me from the train was “You run. I know you will stay alive, you have the Belzer Rebbe’sRebbe: the chief rabbi of a Chassidic group. He is treated with veneration and often consulted in a wide variety of matters, including business, marriage, and religious concerns. The position is often inherited, and many dynasties were named for the cities in Poland and Russia in which Chassidim resided. Source: Binyomin Kaplan. blessing.” He was very religious and he believed this.

I was born in a little city in Poland named Oleszyce. Our community consisted of 7,000 families, half of them were Jews. My father, Israel Vogel, was the head of the Jewish community, the head of the KehillahKehillah: a Jewish community residing in a particular place. Designated leaders were responsible for the welfare of the community including education, burial and charity.Source: Binyomin Kaplan. .

In our part of Poland there was a famous Rabbi, the Belzer Rebbe. When I was born there was a big fire in the Rebbe’s house. He had many invitations to stay with people while his house in Belz was being rebuilt. His personal secretary, his Gabbai, went to look at all these places and chose ours. Our house was big enough to accommodate the Rebbe’s household. This was a great honor. He lived with us for three years.

At this time I was an infant in the cradle. My mother had lost four children. We were supposed to go live in a house we owned next door. My mother refused to move me out of our main house until the Belzer Rabbi blessed me. It was said that he gave me a Special BlessingSpecial Blessing: Rebbes are often asked to give blessings, and the wording of this blessing may have been unusually lengthy or different in some other way from the usual or familiar wording. Source: Binyomin Kaplan. . The whole city knew about this.

My father had a business of distributing religious articles. The occupation of a majority of the older Jews in our community was to make these articles, like Torahs and tefillin. I was interested in how they were made. They would stretch animal skins on a frame to make the parchment. The parchment would be cut into sheets. Sofers or scribes would then write the letters on the parchment. It took a scribe an entire year to write a Torah. They sewed the parchment sheets together into the scrolls with threads made of animal sinews. My father could recognize the handwriting of all of his scribes. Every week they brought their work to my father to get paid. He would then distribute the religious articles to buyers in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Rumania and later, after my brother emigrated, to the United States.

My mother, Ita Prince, was an orphan. The family she lived with was too poor to afford a dowry, and in those days it was hard to get married without one. My father was a widower with six children. My mother was 18 and my father was 34. They matched my mother up with my father because he was rich and because he promised to take in all her sisters and provide dowries for them. She did not want to marry him, but she had no choice. Her foster family said, “If you do not marry him you will have to provide for yourself and your three sisters.” It was a business proposition. My mother had eight children. I was the oldest child. I felt sorry for my mother because she was always pregnant.

At that time it was considered unimportant for a girl to have an education. The government gave you only a basic education, and after that you had to pay. My father educated the boys. After I completed seventh grade my father did not think I should go to high school. I went on a hunger strike. I did not eat and I locked myself in the room until my father agreed that I could go to high school. I had also gone to cheder to get a religious education.

In our city everybody was observant. Everyone went to synagogue and everyone ate kosherKosher: a system of rules and laws (the laws of kashrut) which for Jews govern the preparation and consumption of food.

Eating and drinking are for Jews religious acts where man takes from the bounty of God. Certain items are forbidden as food including blood, pork and fish without scales (e.g. shellfish). Other foods can be eaten separately but not together at the same meal. For example, milk cannot be eaten with meat, but each is a permissible food to be eaten separately within its own family of foods. The rules of kashrut are complex and in cases of doubt a Rabbi is consulted to make a decision according to the law.Source: Rosten, The Joys of Yiddish. . On ShabbosShabbos: the Sabbath, the weekly holiday that commemorates the day of rest that God took after creating the world in six days. Shabbos begins at sundown on Friday night with the lighting of candles, the blessing of wine and the saying of prayers. Afterwards a festive meal is eaten. Shabbos ends with nightfall on Saturday. No work can be performed, and the day is to be spent in rest and prayer. Source: Binyomin Kaplan. the men wore streimelsStreimel: a round fur hat worn by Chassidic Jews. Source: Binyomin Kaplan. . When it was time to go to synagogue on Friday night, the shammes would holler in the street or knock on the doors.

The Jews and the non-Jews in our town did not mix socially, only in business. The anti-Semitism was very strong; we felt it all over. The gentile children did not want to associate with us, and they called us names. The Jewish children were not permitted to take part in school plays. The Christians were told that the Jews killed Christ. On Easter they would throw stones at us. However, there were no pogromsPogrom: (Yiddish from Russian “devastation” or “destruction” from the roots po “like” and from gram “thunder”), the killing and looting of innocent people usually with official sanction, most often applied to Jews. Source: Webster’s Third International Dictionary Unabridged. at this time, before the Germans came into Poland.

We were aware of the Nazis and events in Germany from the newspapers. I remember the incident at Zbaszyn when the Polish citizens were expelled from Germany and were forced to return to Poland. This led up to KristallnachtKristallnacht: the Night of Broken Glass, was a pogrom organized by the Nazis which took place in Germany and Austria in 1938. Hundreds of synagogues were burned and thousands of Jewish shop windows were broken. “Kristallnacht” refers to the broken glass from the shop windows.

On October 29, 1938 the German police began driving 20,000 Polish citizens into the no-man’s land between Poland and Germany near the Polish town of Zbaszyn. On November 7, 1938, in Paris Herschel Grynszpan, a Jewish youth whose parents were among the expelled, shot Ernst vom Rath, a German diplomat.

The Nazis used this as a pretext for a pogrom against the Jews. On November 9 and 10, in all parts of Germany and in parts of Austria, Nazi storm troopers set fire to hundreds of synagogues and destroyed thousands of Jewish businesses. Around 100 Jews were murdered and 30,000 Jewish men were put into concentration camps. The Jews were fined 1,000,000,0000 marks to pay for the damage that was done to them, not by them. Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. , which happened in Germany. I remember that one refugee family did not have a place to live, and my father gave them a room.

Somehow we did not believe Hitler would come to Poland. Until the last minute people did not believe that the Germans would invade us. The Polish soldiers used to sing patriotic songs. They would not give up an inch of our Polish soil to the last drop of their blood. They sang songs about fighting for the port of DanzigDanzig: (Polish Gdansk), a city on the Baltic Sea, held alternatively by Germany and Poland.

After WWI Danzig was made a “free city” under the auspices of the League of Nations. This gave Poland access to the sea and cut off East Prussia from the rest of Germany. Over ninety percent of the population was German and wanted to be re-united with Germany.

In the elections of 1933 the fascist National Socialists became the leading political power. Anti-Semitic policies were enforced. Danzig was reunited with Germany on September 1, 1939 with the outbreak of WWII.Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. .

People did not believe that the Germans would come until they saw the airplanes. It was so sudden. In a couple of days the Germans occupied the whole of PolandPoland’s Defeat: On September 1, 1939, German troops invaded Poland. Polish defenses crumbled before the German onslaught of tanks, motorized vehicles and attacks by dive-bombers on the civilian population. The German theory of Blitzkrieg (“lightning war”) involved massive concentrated attack.

After two weeks Germany controlled western Poland except for Warsaw, which held out for two more weeks. Meanwhile, on September 17, 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east according to the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact signed in August 1939, which divided Poland into spheres of interest for each country. Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. . Then there was not anything one could do. It was too late. The Germans and the Russians had a treaty, the German-Soviet Non-Aggression PactGerman-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact: an agreement between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on the eve of WWII. The pact was a temporary alliance of adversaries which secured Hitler’s eastern front and bought time for Soviet military preparedness. The agreement was breached by Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union less than 2 years later.

The Pact was signed one week before Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939. It divided Poland into two spheres of influence with the eastern parts being of interest to the Soviet Union and the western parts being in the sphere of influence of Nazi Germany. The dividing line was along the Narew, Vistula and San rivers.

By a special protocol the Baltic states were recognized as part of the Soviet sphere, with Lithuania’s claim to Vilna acknowledged by the Germans. The pact which was supposed to last 10 years was terminated by the invasion of the Soviet Union by Germany on June 22, 1941.Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. , which divided Poland at the River San. Because our town was on the Russian side, the Germans occupied our part of Poland for just two weeks. Then, according to the Treaty, the Russians came in. Until 1941 the Russians were in charge.

I still had a year left to finish high school. But my father could not continue his business because the Russians did not permit the practice of religion. As the oldest child I had to take a job to support the family. Jobs were hard to get. The Russians gave the first jobs to poor people and to working people. Because my father was considered a rich businessman, he was called a capitalist. As the daughter of a “capitalist” I could not get a job. So I wrote a letter to Stalin. I wrote him that we were a large family and my father was too old to work. I received a reply from his office, and I was given a job. They wrote it up in the local newspaper. I started out as a secretary and advanced to assistant assessor in the local internal revenue office.

We did not expect anything to happen. One Saturday evening in June 1941 we went to sleep. About 6 o’clock Sunday morning we heard gunshots and went out to see what was happening. German motorcycles were going down the main street. Soldiers were shooting right and left. Whoever was on the street was killed right away. This is when our problems began.

The Jews were not permitted to keep a job. People started to trade their belongings with the farmers for food. Potatoes and flour were more important than money. If someone had savings in the bank, all the money was confiscated. If someone had cash at the house, it did not last too long. Best off were the people who had stores and who could hide the merchandise.

The first thing they did was to make a JudenratJudenrat: a Jewish council created under German orders which was responsible for internal matters in a ghetto.

It was required to provide Jews for forced labor and to collect valuables to pay collective fines imposed by the Germans. The members of the Judenrat believed that by complying with German demands that could ameliorate the harsh realities of German administration. Frequently, they were able to set up hospitals and soup kitchens and to try to meet basic sanitary needs in the ghetto.

In the beginning the members tried to resist German pressure. However, as time went on, the Judenrat was forced to deliver Jews to the deportation trains that were bringing them to their deaths. Under pressure many members of the Judenrat cooperated with the Germans. However, there were many cases of resistance, of resignation, of support for the partisans, and of committing suicide rather than bending to German pressure. Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. . A few Jews became responsible for the entire Jewish community. To these people they gave orders which they had to pass on to us. Every day there was a different decree. We had to put on armbands so we would be recognized as Jews. Our armbands were white with blue Stars of David sewn on. Every day orders came for people to go to work at hard labor or to do work like cleaning toilets. The Judenrat had to deliver the number of people they required.

Already it was a fight for survival. We had to do what they wanted. If we did not, we would be killed immediately. We did not have a newspaper or a radio so we did not know what was going on in the outside world. We just hoped to stay alive and that the war would end before they would do something to us.

We were not allowed to walk down the sidewalks, but had to walk down the middle of the street. The street in our town was not paved. When it rained it became a street of mud. Once my mother forgot and walked on the sidewalk. A young walked by, a Ukrainian man who was a teacher. He had helped my brothers with their homework and had come to our house. He went and hit my mother when he saw her walking on the sidewalk. My mother came in and cried. She said, “If a German had done it, I would have said nothing. But this man should have been an intelligent person: he came into my house and I fed him.”

Even your friends could turn against you. It was as if anyone could pick on the underdog. I did not understand. I felt degraded. There were times when I envied a dog. A dog has his master who takes care of him and feeds him. We were outside the law. Anyone could do with us as they wanted.

I was luckier than most people under the Germans. I understood the tax books. For almost a year I was sitting in city hall with the armband working on the tax books. I worked for them until they could train somebody else. I did not receive any pay. I got bread, which was better than getting money. When I brought the bread home, I gave everyone a piece. My little brother looked for crumbs on the floor because he was hungry and wanted more, but nobody could have more. Now I feel so guilty. I hit him because he took the crumbs from the dirty floor.

In those days the way they delivered messages was by a city drummer. He beat his drum calling out “Ja wam tu oglaszam”” I have an announcement for you.” In our town the drummer’s name was Pan Czurlewicz. He wore a uniform like a policeman. He came to our street drumming and calling until everyone came out of their houses. “All the Jews must assemble in the city square,” he said, “If they find someone missing they will be shot.”

When we arrived at the city square, we saw a fire in the middle of it. The whole inventory from the synagogue was burning, the prayer books, the torah scrolls, everything was burning. The German soldiers pushed the young girls up to the old men and made them dance around the bonfire. When we looked up we saw that each of our town’s three synagogues was on fire.

All around us our neighbors and friends were watching and laughing at us like they were at a show. This hurt us more that what the Germans did. After the fire burned down they told us to line up and parade through the whole town so everyone could see us. This I will never forget.

We were living in conditions of hunger and fear, but we were still in our own homes. People made hiding places in their houses to hide from the Germans. Our hiding place was in the attic behind a double wall. Whenever we saw the Germans, we would run to the attic and hide. Even the little children understood that if they made noise it was a matter of life and death.

This continued until September 1942. One day the drummer came. He announced that all the Jews had to take what they could carry and walk the seven kilometers to the next town of Lubaczow. There was a ghettoGhetto: an enclosed district where Jews were forced to live separate from the rest of society.

The concentration of Jews in ghettos was a policy implemented by Germany in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. The establishment of ghettos was often the first stage in a process which was followed by deportation to concentration camps and selection for extermination or for forced labor. Forcing Jews into ghettos required their ingathering from surrounding areas and their segregation from local populations. Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. there.

All the Jews of Oleszyce and the neighboring villages were moved to the ghetto in LubaczowLubaczow Ghetto: located in the town of Lubaczow near Przemysl, Poland. The ghetto was established in October 1942 and liquidated in January 1943. Seven thousand Jews were kept in apartments located in the center of town. Five to six families lived in each apartment. Twenty-five hundred were shipped to the extermination camp at Belzec. The rest were shot and buried in Lubaczow. Source: Mogilanski, The Ghetto Anthology. . The ghetto was the size of one city block for 7,000 people. We slept 28 people in a room that was about 12 by 15 feet. It was like a sardine box. People lived in attics, in basements, in the streets--all over. We were lucky to have a roof over our heads; not everyone did.

It was cold. In one corner there was a little iron stove but no fuel. We were not given enough to eat. The children looked through the garbage for food. There was not enough water to drink. There was one well in the backyard, but it would not produce enough water for everybody. To be sure to get water you had to get up in the middle of the night. Once I had a little water to wash myself, and my sister later washed herself in the same water. Some people started to eat grass. They would swell up and die. Because of the unsanitary conditions people got lice and typhus. My brother Pinchas got night blindness from lack of vitamins. Every day a lot of people died. It was a terrible situation. People were depressed. There was nothing to do. They waited and hoped and prayed.

Then, beginning on January 4, 1943, the GestapoGestapo: (Geheime Staatspolizei; Secret State Police), a police force, often members of the SS, who were responsible for state security and the consignment of people to concentration camps.

The Gestapo’s main tool was the protective custody procedure which allowed it to take actions against “enemies of the Reich.” With Jews and Gypsies the Gestapo simply rounded them up; it was not necessary to give even the appearance of legality to their actions.

By 1934, Heinrich Himmler became head of the Gestapo throughout Germany. Under Himmler’s leadership the Gestapo grew enormously. The Gestapo was a bureaucratic organization with many sections and branches. In 1939 the Gestapo was consolidated with other police forces to form the RSHA (Reich Security Main Office). The RSHA, including the Gestapo and the SS, assumed the task of enslaving the “inferior races” and carried out a major role in the “Final Solution”.

Besides Himmler, other notables in the organization were Reinhard Heydrich the architect of the Final Solution until his assassination by Czech and British agents, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, who was tried and hung at the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials, Adolf Eichmann, who was in charge of Jewish deportations to the death camps and later tried in Israel, and Heinrich Muller.Source: USHMM, Historical Atlas of the Holocaust. and the Polish and Ukranian police started to chase all the Jews out from their houses. The deportation took several days. People ran and hid. The Jewish policeJewish Police: (Judischer Ordnungsdienst), the Jewish police units organized in the ghettos by the Judenrat. The Jewish police collected people for forced labor, guarded the ghetto fences and gates and eventually seized people for deportations.

There was often misconduct and corruption among the police, and they were regarded with apprehension by the ghetto community. They and their families were, at first, exempt from deportation, but this exemption was rescinded when their usefulness to the Germans ceased. Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. helped to find the people in hiding. They had been promised that they would stay alive if they cooperated.

We knew where we were going. A boy from our town had been deported to Belzec camp. He escaped and came back to our town. He told us that Belzec had a crematorium. Deportation trains from other cities had passed by our city and people had thrown out notes. These notes were picked up by the men forced to work there. The notes said, “Don’t take anything with you, just water.”

They took us to a cattle train. People started to run away from the train, but they were shot. Once on the train we had to stand because there was no room to sit down. A boy tore the barbed wires from the train window. The young people started to jump out of the window. Many jumped. The SSSS: (Schutzstaffel, Protection Squad), originally Adolf Hitler’s bodyguard, it became the elite guard of the Nazi state and its main tool of terror. The SS maintained control over the concentration camp system and was instrumental in the mass shootings conducted by the Einsatzgruppen.

Led by Heinrich Himmler, its members had to submit with complete obedience to the authority of the supreme master, Hitler and himself. SS officers had to prove their own and their wives’ racial purity back to the year 1700, and membership was conditional on Aryan appearance.

In the charter of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg (commonly known as the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials) the SS was held to be a criminal organization. Its members were considered war criminals involved in brutalities and killings in the concentration camps, mass shootings in the occupied countries, involvement in the slave labor program and the murder of prisoners-of-war. Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. on the rooftop of the train shot at them with rifles. My father told us, the oldest three, “Run, run--maybe you will stay alive. We will stay here with the small children because even if they get out, they will not be able to survive.” To me he said, “You run, I know you will stay alive. You have the Belzer Rebbe’s blessing.” He was very religious and he believed this.

My brother Berele jumped out, then my sister Hannah, and then I jumped out. The SS men shot at us. I landed in a snowbank. The bullets did not hit me. When I did not hear anything anymore, I went back to find my brother and my sister. I found them dead. My brother Berele was 15. My sister Hannah was 16. I was 17.

I took off my star and I promised myself that never again would I ever wear a star. I ran back to the city where we lived. We had a Gentile friend there, a lady to whom we gave a lot of our belongings. She was scared to keep me. Gentile families who were found to be hiding Jews would be killed. She hid me behind a cedar-robe in the corner. I was standing there listening to people come in. They were discussing how they were killing the Jews, how the Jews were running away, who had been shot. It was a small city. They felt sorry for the Jews. It was a sensation, a thing to talk about. They felt sorry but they forgot right away.

In the evening when it became dark she gave me half a loaf of bread and 25 Polish zlotys. She told me to go. I went to another family’s house that I knew who lived close to the woods. He was a forester. When I worked with the taxes, I had helped them. They were afraid to let me in. It was already dark. I could not walk. It was freezing cold. There was snow. I was not well dressed. I went in the barn where they had a newborn calf, and I lay down with it to keep me warm. About twelve o’clock the wife came to look at the calf. She saw me and felt sorry for me. She let me come and sleep in the house, but in the morning she told me to go.

I wanted to go to the train station, but I was afraid to go in our city because everybody knew me. So I went to the woods and walked to the next station 32 kilometers away. At that time it was thought that there were partisansPartisans: guerrilla forces operating in enemy occupied territory. In World War II there were partisan groups of various political, national and religious complexions operating mainly in eastern Europe and the Balkans. The major areas of activity in eastern Europe were in Belorussia, in Lithuania and in the Ukraine. There were also Jewish underground movements that functioned within the ghettos and camps of Poland. Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. in the woods. People were afraid to go in the woods, but I was not afraid. I was walking in the deep snow, and in the evening I came to the station in Jaroslaw.

At the Jaroslaw station I bought a ticket for Cracow. I figured that Cracow was a big city with a big Jewish community. Maybe the ghetto would still be there. In the train station I saw the person who took over my job at the internal revenue. I was frightened that she might recognize me. I kept walking around the block until the train came. Then I got on the train. This was another situation. I did not have any documents. The lady that gave me the bread had given me some papers from her daughter, but they were not good enough. There were identification checks on the train. Every station I would move to another wagon.

In Cracow I spent two days and two nights living in the train station. There was a curfew at night because of the war. People who came into the city late had to stay in the train station until morning, so there were always a lot of people there. I moved around a lot so people would not recognize me, from one bench to another, from one room to another. It was a big station. But I did not have any money, and I did not have any bread. I had never been to CracowCracow: (Krakow), one of the oldest and largest cities in Poland, and the location of one of the most important Jewish communities in Europe.

On March 20, 1941 the ghetto was sealed off. It was confined to a small area and heavily overcrowded. By the end of October 1942 after the second deportation (Aktion)the ghetto was split into two parts. On March 13, 1943 the residents of part “A” were sent to the Plaszow labor camp and on March 14 the residents of part “B” were transferred to Auschwitz-Birkenau and gassed there.

There was a resistance movement in the ghetto. Their most famous operation was an attack on the Cygeneria cafe in which 11 Germans were killed and 13 wounded. Attempts were made to join in partisan activities in the surrounding area but the resistance encountered problems because of their isolation and because of the hostile attitude of units of the AK (Armia Krajowa Polish Home Army) which did not take kindly to Jewish partisan operations. Source: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. before. I did not know where the ghetto was. I did not see anybody with an armband, and I was scared to ask someone where the ghetto was.

I walked and walked. I was hungry. I figured the only thing to do was to jump in the river. I came to a market place, a farmers’ market. I could hear running. They closed up the market place and took all the young people aside. I could hear the girls and boys talking. They were catching boys and girls and sending them to work in Germany. Nobody would go work freely in Germany; they had to use force. This was how they rounded up the people. I was very glad that I was caught with those people. I was caught as a Gentile and not as a Jew.

They took us to an old school at Number 4 Wolska street. First they sent us to take baths, and they disinfected our clothes. A lady inspected our hair; because I had been in the ghetto, I had lice. She cut my hair short and put something in it. Next they sent us to doctors. If you had certain kinds of sicknesses, you would be relieved.

I prayed to God that they should not find anything wrong with me--after such a long time in the ghetto, after the malnutrition. Thank God, I passed the physical. If I had been a boy, I could not have passed. None of the Polish boys were circumcised, but the Jewish boys were. A Jewish boy would have been recognized by the doctors right away. I assumed the identity of a Polish girl, Katarzyna Czuchowska, a name I made up. I took a different birthday, May 12th.

We were put on a train and taken from Cracow to Vienna. They sent us to a place where the German farmers came to pick up workers. It was something like a slave market. One family liked me and took me to their farm, which was on the border with Czechoslovakia in the Sudetenland. The farm was a bad place because the husband was at home and he was a very mean person. The neighbors said that he avoided the draft by bribing someone. He made anti-Semitic remarks, even though he did not know I was Jewish.

After a year I got sick. They transferred me to a smaller farm where there were nice people. There were no males there, and I had to carry sacks of grain. At Christmas, when the husband came home on leave, they made homemade wine from their vineyards. The husband got drunk and he began to curse Hitler, “Hitler, you so-and-so! If it were not for Hitler, I would be home with my family.” I was scared someone would hear him, so I closed the door so nobody would come into the house.

I was scared that they would find out I was Jewish. I was not afraid of the Germans because I was not different looking from anyone else. But I was afraid of my friends, the Poles. I was scared that one of them would recognize me. They were country girls, and I was afraid that they would figure out how much more educated I was.

I was the letter writer for everybody. If someone needed to write a love letter, they came to me. The Poles got letters from their families and packages of clothes. My letters were returned. I made up the excuse that my family was resettled and they did not know where I was. After a time when I saw that nobody recognized me, I felt secure.

Then a terrible thing happened. Before Easter, Marie, the farm lady I worked for, told me that I had to go to confession. I was a religious Jewish girl, and I did not know what Catholic girls did at confession. I lay awake nights worrying what I would do until I came up with a solution.

My Polish friends did not speak German, which I had picked up easily because I knew Yiddish. My friends were going to go to confession at the Slovakian church, where they spoke a language close to Polish. I asked Marie to let me take confession at her church in the German language. She showed me the prayer book where I had to confess my sins. I figured if I did not say the words exactly right, the German priest would not be suspicious because I was just a Polish girl. So I made up some sins and went to confession. My heart was pounding; I was so scared. I saw what other people were doing, and I imitated them. I went up to the German priest, and he put something on my tongue. Somehow I blacked out; it must have been the fear. When I came to, Marie asked me why I was so pale. I made up the excuse that I was weak from fasting. Later on everything went smoothly.

The worst part was when I tried to go to sleep. In the daytime I did not have time to think. I got up at five o’clock in the morning, milked ten cows, then went into the fields. But at night I was afraid to sleep. I dreamed about my family and my friends. I had horrible nightmares: I dreamed I saw my whole family with the Germans running after us. I hid but I could not escape from them. I wondered if my family were dead or alive. I dreamed I saw my dead sister and brother on the cattle train to Belzec. I woke up shaking in a cold sweat. At that time I prayed to God. I promised myself, “If I will survive, I will return to the religion of my parents. I will observe.” And that’s how I survived.

They brought sixty Jews to a big farm to work. There were guarded by the SS. One day I passed three of them, and I felt such an urge to talk to them. I saw that other boys and girls were talking to them, but I was scared that if I talked to them, I would get emotional or reveal something, and they would recognize me. I do not know what happened to those people.

In May 1945 the Germans started to draw back, and one day the Russians came in. I was still scared to tell anyone I was Jewish. I looked at the Russian soldiers to see if I could recognize anyone who was Jewish, but I didn’t.

Now came the time that I could help my people, the German farmers. The Russians started to rape the German women. When they came to our door, I spoke to them in Russian. They stationed a Russian captain in our house. He saw to it that nothing happened to our family.

I wanted to go back to Poland. I figured that maybe I would still find somebody alive. It was a long journey back to Poland. The mail started up. I had a brother and sister from my father’s first marriage who were alive. He had immigrated to the United States in 1933, and she had gone to Russia. He wired her and she came and got me and took me to Breslau (Wroclaw). We could not go back to our city because Russia had taken that part of Poland. I had written to a friend and not one Jew went back to our city. I learned later that from my whole city of about 3,000 Jewish families, just 12 people survived.

The Red Cross had lists of people who had survived, but we could not find anybody from our family. My half-brother attempted to get me a visa to the United States, but there were quotas. I got a transit visa to Sweden. Meanwhile, from the Red Cross lists I found a friend from Oleszyce who had been in Auschwitz. She was the only other person who jumped from the same train as I did and lived. Her fiancee had met my future husband at the train station in Cracow. My husband was in the Polish army. He and I were childhood friends from Oleszyce. Her fiancee invited my husband to come to their wedding, which was two weeks before I was supposed to go to Sweden, but they did not tell me anything about him.

At the wedding Henry walked in--He did not know that I had survived--I did not know that he had survived. I almost dropped from the chair. I thought I was seeing a ghost. Henry right away asked me to marry him. I said, “No, Henry, I have to wait; I am going to Sweden.” Henry went with me to Warsaw to catch the first airplane that was going from Warsaw to Stockholm after the war. Henry said, “I will come to Sweden.” Four weeks later Henry came illegally on a coal boat to Sweden. He paid a sailor who smuggled him onto the boat.

At that time most of the survivors were single. People married people that they did not know just to get somebody, just to have a family. When Henry and I were young children in school, he would come to our house under my window and talk to me. We were friends. Not boyfriend and girlfriend. I was too young. But we were attracted to one another.

When the Swedes let Henry out of quarantine, he asked for political asylum. He did not want to be in Poland, a communist country, in a communist army. A Rabbi married us three weeks later on Christmas Eve. I did not even have a coat. I had to borrow a coat from the girl next door to go to Synagogue. We took a furnished room and went to work in a restaurant. We were dishwashers. Henry washed the big pots and I washed the glasses. We lived on one salary and with the other we bought things that we would need for the house.

After three months I got a job in a factory making blouses, and Henry got a job in a tailoring factory. No one gave us anything; we started out from nothing. We worked our way up with our ten fingers. Henry learned tailoring in no time. They sent him to a school to learn to be a foreman. He got a high school degree; he took correspondence courses; he learned English. After three years my eldest daughter was born.

We came to the United States on May 2, 1954, when our quota came. After eight years in Sweden it was difficult to adjust to life in New York City. It was difficult for me not knowing the language. When I came to the United States I spoke Yiddish, Hebrew, Polish, Russian, German, and Swedish, but not English. I was pregnant and stayed at home. My oldest daughter came home with her school books--”See Dick run.” I learned English by helping my daughter with her homework. I tested her on spelling, and she tested me. As soon as I learned the English language, I adjusted. After seven years in New York, we thought we would like it better in a smaller community. We came to New Orleans in 1962. Eventually, my husband started his own tailoring business. I had two other children, both girls.

There are times when I ask myself, “Where was God when my parents were taken away from me? When my youngest brother shouted, which I still hear him screaming, I want to live too!”’ When they took us away, he shouted, “I want to live, I want to live!” This picture will never, never in my life disappear from my eyes. A lot of times when I lie down, I still hear that voice. He was 3 years old. Even though they were that small, the little children knew what was happening to them. And I ask myself a lot of times, “Where was God? Where is God?” I don’t try to search any deeper because I think without religion it would be harder for me to live.

If you lose your parents at any age, it hurts. To lose your parents in that way, at that age, and to be alone in the world... If you cannot grieve right away, it stays with you for your whole life. You need compassion to be able to talk out your grief. Time is the best doctor. As the days and weeks and years go, it grows weaker and weaker. But you never forget. I tell my students that they should cherish their parents and obey them. A parent is always at your side.

In Poland, after the war I was sick emotionally and physically. I had to go to a doctor to get shots to gain weight. In Sweden I went to a psychiatrist because I could not get over those terrible nightmares. Today I see that when there is a disaster, they send people to a psychiatrist or a psychologist. We had to work out our own problems. As parents we were overprotective to our children. My eldest daughter was accepted at an Ivy League college, but I was afraid to let her go away from home to school. We were afraid to let our children know too much about our past.

I taught Hebrew and prepared children for their Bar Mitzvahs. A friend encouraged me to go to college. In 1985 I graduated from the University of New Orleans. It was my children that made me talk. In the beginning I did not talk to anybody. I did not tell anything. My daughter had to write a paper for school, and she got me to talk. Now, Henry and I go to schools to talk with students about the Holocaust. That is how life goes on.

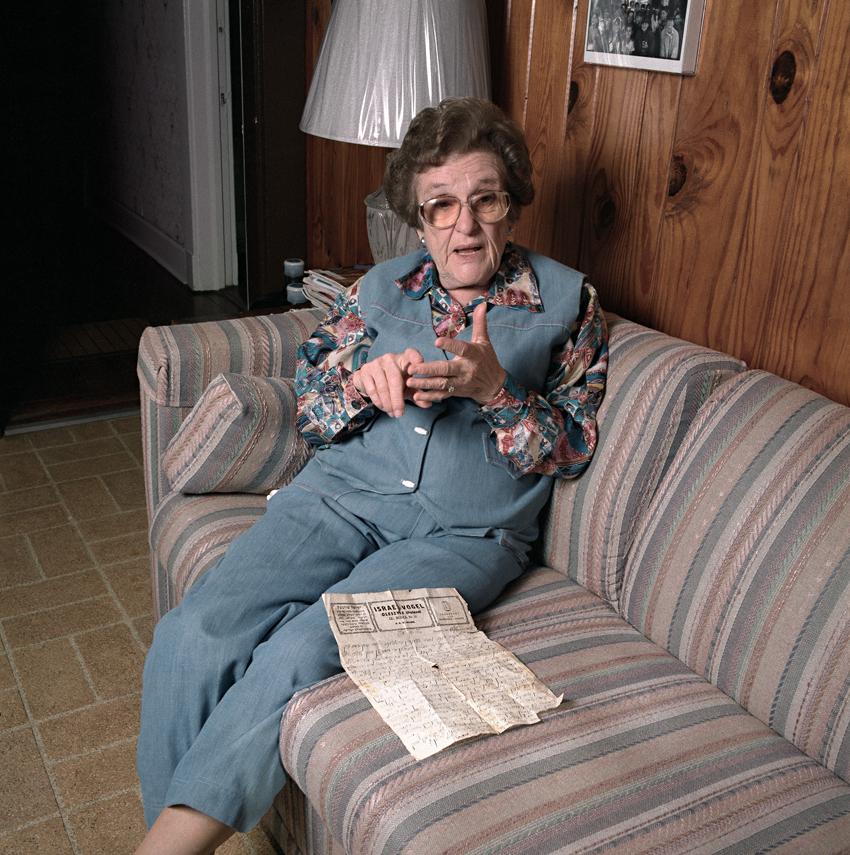

Eva Galler explains how the persecution of Jews began as a step-by- step process with measures of increasing severity. The Jews did not foresee that it would end in mass extermination. Next to her is a letter written by her father on March 3, 1938, during the Anschluss of Austria with Germany: “By now you have heard that Vienna has been occupied by the Germans. Unfortuantely, we are dancing at the same wedding. I am very nervous.”

Photo Credit: John Menszer

Reb Aharon (center) was the son of the Belzer RebbeRebbe: the chief rabbi of a Chassidic group. He is treated with veneration and often consulted in a wide variety of matters, including business, marriage, and religious concerns. The position is often inherited, and many dynasties were named for the cities in Poland and Russia in which Chassidim resided. Source: Binyomin Kaplan. who blessed Eva Galler, Reb Yissochor Dov. The Chasidic line is dynastic. At the right of the photograph is Eva Galler’s 2nd cousin, Shalom Vogel, who was Gabbi, or assistant, to the rabbi.

Photo Credit: P. Wyschogrod

Israel Vogel was a dealer and manufacturer of religious articles. Oleszyce, the little town he lived in, was known as a manufacturing center for such articles. Pieces of parchment that were not suitable for torahTorah: the scroll containing the first five books of the Jewish Bible or Five Books of Moses. The Torah contains the essence of the Jewish religion, including the 613 commandments or mitzvot. The highest ideal for every Jew is the study of Torah.

The verses must be written in hand by a qualified sofer, or scribe. The scribe must take a ritual bath before beginning to inscribe a Torah and rules dictate which mistakes can be corrected and which mistakes require starting over. The Torah scrolls are stored on the East wall of the synagogue facing Jerusalem in the Ark or Aron Kodesh. Above the Ark hangs the ner tamid or eternal light.

Another major usage of the word “Torah” refers to classical Jewish religious texts in general and to the total corpus which they form. Hence, someone studying Talmud, Tanach, Midrash or Codes is also “learning Torah.” Source: Rosten, The Joys of Yiddish. scrolls were made into drumheads. He had a sideline in the music business.

Photo Credit: Eva Galler

Ita Vogel was Eva’s mother. She was an orphan and married Israel Vogel to provide dowries for her sisters.

Photo Credit: Eva Galler

Eva Galler at age 14. She was one of 8 children. Her father had 6 children by his first wife.

Photo Credit: Eva Galler

Eva Galler’s half-brother, Morris, married Dora, then living in the United States, who returned to Poland to find a suitable husband. The couple left Poland just before the outbreak of war. Left to right standing: Eva, then 15, is at the extreme left. Skip two, then her father Israel and mother Ita Vogel. Skip one, Dora in veil with Morris. Then Eva’s half-brother Hirsh. Skip to Eva’s Uncle Abraham Vogel in hat at right. Left to right seated: a niece, then sister Hannah. Sitting in front: brother Azrael, sister Devorah in bow, then two cousins. Seated in back: a nephew and niece, then brothers Pinchas and Berele.

Photo Credit: Eva Galler

Letter to Eva Galler’s aunt and uncle who married in Israel. ISRAEL VOGEL OLESZYCE (Poland), MANUFACTURER AND DISTRIBUTER OF TEFILLINTefillin: (phylacteries), small leather boxes which are bound to the arm and the head with leather straps during prayer. They contain parchments on which are hand lettered four passages from the Torah. The passages recite the commandments to place a sign on the hand, upon the heart and between the eyes. Source: Rosten, The Joys of Yiddish. , MEZUZAH, LEATHER STRAPS, TZITZIT, THREAD FOR PARCHMENT, SHOFARS, SPECIAL TEFILLIN, TORAHSTorah: the scroll containing the first five books of the Jewish Bible or Five Books of Moses. The Torah contains the essence of the Jewish religion, including the 613 commandments or mitzvot. The highest ideal for every Jew is the study of Torah.

The verses must be written in hand by a qualified sofer, or scribe. The scribe must take a ritual bath before beginning to inscribe a Torah and rules dictate which mistakes can be corrected and which mistakes require starting over. The Torah scrolls are stored on the East wall of the synagogue facing Jerusalem in the Ark or Aron Kodesh. Above the Ark hangs the ner tamid or eternal light.

Another major usage of the word “Torah” refers to classical Jewish religious texts in general and to the total corpus which they form. Hence, someone studying Talmud, Tanach, Midrash or Codes is also “learning Torah.” Source: Rosten, The Joys of Yiddish. , TORAH SPINDLES, DRUMHEADS Dated March 18, 1938: Dear Brother-in-law and Sister-in-law: First of all I want to thank you for the two letters that we recieved. Ten days ago I sent you a tallisTallis: a prayer shawl worn during religious services. Source: Rosten, The Joys of Yiddish. as a sample. Answer right away if you received it and if you had to pay duty. It is a gift. I added a bunch of silk tzitzit and they are kosherKosher: a system of rules and laws (the laws of kashrut) which for Jews govern the preparation and consumption of food.

Eating and drinking are for Jews religious acts where man takes from the bounty of God. Certain items are forbidden as food including blood, pork and fish without scales (e.g. shellfish). Other foods can be eaten separately but not together at the same meal. For example, milk cannot be eaten with meat, but each is a permissible food to be eaten separately within its own family of foods. The rules of kashrut are complex and in cases of doubt a Rabbi is consulted to make a decision according to the law.Source: Rosten, The Joys of Yiddish. . For you, dear brother-in-law I sent a nice tallis and you should wear it with pleasure. God should not forget you. You should have a good and steady job and should be able to afford everything, and your wife should not have to work. By now your have heard that Vienna has been occupied by the Germans. Unfortunatey, we are dancing at the same wedding. This has cost me thousands of zlotys which are owed to me. I am very nervous and cannot write anymore. Regards and kisses. These are the weeks of your honeymoon. Yours Truly, Israel

Photo Credit: Eva Galler

Eva Galler’s aunt Helen moved to Israel and married uncle Joseph. The children in the Galler’s household sent greetings to the betrothed, and this letter was recovered after the war. YiddishYiddish: the language of East European or Ashkenazic Jews. Yiddish is to be distinguished from Hebrew, which is the language of Jewish prayer and the official language of Israel.

Yiddish is descended from the form of German heard by Jewish settlers who came from northern France to Germany a thousand years ago. Almost all East European Jews before WWII understood Yiddish and many would have spoken it at home. Some East European Jews attended schools taught in Yiddish. It was estimated that in the 1920’s about two-thirds of the Jews in the world could understand Yiddish. Although Yiddish used to be a lingua franca or common language for Jews, this is not true today.

Yiddish possesses an incomparable vocabulary to express shades of feeling and a rich storehouse of characterization names, praises, expletives and curses. A Yiddish literature developed that matured into a diverse and sophisticated body of work. Perhaps its most famous exponent was Sholem Aleichem (the pen name of Sholom Rabinowitz 1859-1916). The musical “Fiddler on the Roof” is based on his stories. YIVO, the Yiddish Scientific Institute, was created in Vilna and continues in New York City to further Yiddish research and culture.

The Holocaust had a devastating effect on the Yiddish language because it destroyed most of its speakers. Isaac Bashevis Singer(1904-1991) won the 1978 Nobel Prize for literature for his Yiddish novels and short stories. In 1980, the National Yiddish Book Center opened in Amherst, Massachusetts. Source: Rosten, The Joys of Yiddish. is written in Hebrew characters and reads from right to left: From me, Pinchas Vogel. Dear Helen, What is going on? Are you healthy? Regards, Berele. I would fly to your wedding. I will send you a photo. Regards to you and your husband, Malka. I had a very good report card. I am doing well in school. Malka. The drawing of the man and woman is by Devorah.

Photo Credit: Eva Galler

Hannah jumped with Eva Galler from a death train taking them to Belzec extermination campExtermination Camps: (Vernichtungslager), Nazi camps in Poland in which millions of Jews were murdered as part of the “Final Solution”, as well as hundreds of thousands of Roma (Gypsies), non-Jewish Poles and Soviet prisoners of war.

The 6 extermination camps were Auschwitz-Birkenau, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor and Treblinka. The purpose of these six camps was the systematic murder of human beings and the disposal of their bodies. Killing was done in a factory-like manner by poison gas in gas chambers or gas vans. The bodies were buried in mass graves or burned. The overwhelming majority of victims in these 6 camps were Jews. Sources: Encyclopedia of the Holocaust; USHMM, Historical Atlas of the Holocaust. . She was shot by guards riding on the train.

Photo Credit: Eva Galler

Yissochor Dov or Berele was Eva’s younger brother. He was named after the Belzer RebbeRebbe: the chief rabbi of a Chassidic group. He is treated with veneration and often consulted in a wide variety of matters, including business, marriage, and religious concerns. The position is often inherited, and many dynasties were named for the cities in Poland and Russia in which Chassidim resided. Source: Binyomin Kaplan. who blessed Eva as an infant. Berele jumped with Eva from the death train.

Photo Credit: Eva Galler

Eva Galler’s siblings left to right: Berele, Malka, a Nephew, Devorah and Pinchas. Pinchas suffered night blindness from a vitamin deficiency he acquired in the ghetto and was unable to jump from the death train.

Photo Credit: Eva Galler

Katarzyna Czuchowska was the fictitious identity assumed by Eva Galler to hide her Jewish background.

Photo Credit: Eva Galler

Malka, Hannah and Divorah were sisters to Eva Galler. Malka and Divorah used to entertain guests by singing popular songs. Hannah jumped with Eva Galler from the death train but did not survive. The sisters were standing outside of the Vogel house in Oleszyce, Poland.

Photo Credit: Eva Galler